✅ Early Reporting Creates a Bias Toward Severe Cases

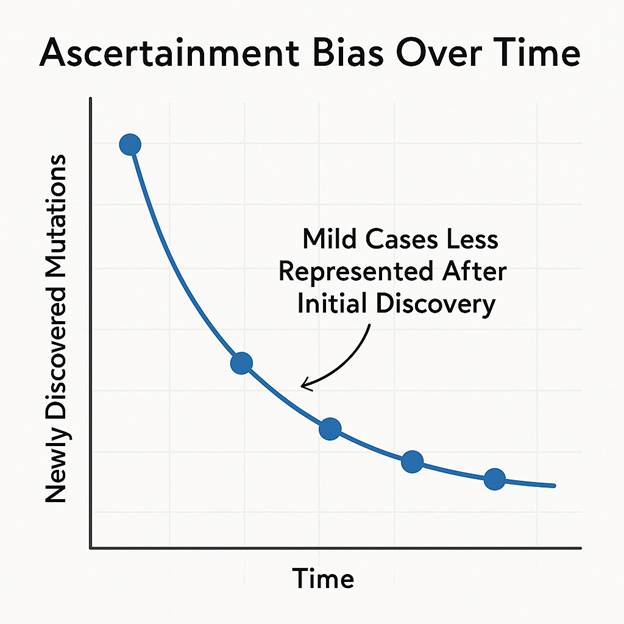

There is a thing called “ascertainment bias”:

- When a mutation like SPAST p.Arg499His is newly recognized (2005-2010), only the most severe or unusual cases tend to get published.

- These are:

- Diagnosed by specialists in rare disorders

- Often found through research-grade genetic testing (like whole-exome sequencing)

- Selected because they stand out

🧠 So the early literature paints a bleaker picture than may actually be true for all people with the mutation, because mild or moderate cases are missed, undiagnosed, or considered “atypical.” They aren’t published — or even identified — yet. This is where a registry like the one created by the Spastic Paraplegia – Centers for Excellence Research Network provides so much value. (SP-CERN – The Spastic Paraplegia – Centers for Excellence Research Network)

📉 The Impact on Prevalence

Because of that reported prevalence may actually underestimate the true number of people with the Arg499His mutation, especially milder or undiagnosed individuals.

- Since genetic testing isn’t yet universal, many people with milder cases or overlapping symptoms (e.g. spasticity misdiagnosed as cerebral palsy or autism) may never be tested for SPAST mutations at all.

So paradoxically early in a mutation’s discovery, the prevalence looks artificially low, and the severity looks artificially high.

🔁 What Happens Over Time?

As awareness and testing expand:

- More mild/moderate cases are found

- Prevalence increases, sometimes significantly

- The overall picture becomes less grim, because milder phenotypes are added to the mix

This happened with many genetic disorders:

- BRCA1/2: once thought to cause only aggressive breast/ovarian cancer — now known to have variable expression

- MECP2 (Rett syndrome): once thought fatal in infancy — now known to have adult survivors with milder forms

🎯 So the early data on Arg499His likely overrepresents severe cases and underrepresents milder or undiagnosed ones, which skews both perceived severity and prevalence.

That’s why:

- Some kids are misdiagnosed with CP or nonspecific developmental delay

- Others may have inherited mutations with reduced penetrance and go undiagnosed

- Literature appears “bleaker” than the full natural history

Another reason why we have to gather together and share our experiences as more of us become diagnosed.

Leave a reply